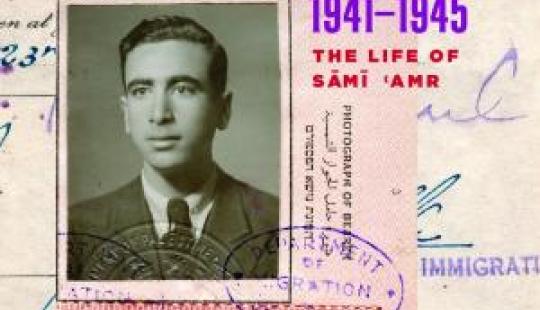

Yawmiyyat Sha‘b Filastini: Hayyat Sami ‘Amr, 1941-1945 (The Diary of a Young Palestinian: The Life of Sami ‘Amr, 1941-1945)

December 5, 2017

A Young Palestinian's Diary

by Kimberly Katz

Foreword by Salim Tamari

Translated by Ibtisam al-Khadra

Edited by Carol Khoury

While there have been a number of historical memoirs published over the past 20 years in Palestinian studies, from such well-known scholars and writers like Edward Said, Raja Shehadeh, Suad al-Amiry, Hanan Ashrawi, and Sari Nusseibeh, scholarship on personal diaries has been less visible. As historiographical artifacts, personal diaries are the individual threads of the fabric of historical context, offering a micro view of testimonial literature that introduces readers to the lives of individuals from Palestinian society across class, location, and time.

A number of recently published diaries in Arabic focus on the late Ottoman to the immediate post-British Mandate period, including the diaries of Ottoman soldier Ihsan Turjman and the well-known educator Khalil al-Sakakini, and offer contrasting perspectives on Jerusalem. al-Sakakini’s daughter, Hala al-Sakakini, also kept a diary about her life in Jerusalem, adding yet another perspective on life in British Mandate Jerusalem (her diary is published in English). Muhammad al-Sharouf’s diary, which begins during the British Mandate period (1943) and ends during the Jordanian period (1962), reflects life in different parts of Palestine due to his work as a policeman, but focuses on his home life in Nuba, a village outside of Hebron. His entries note his frequent forays into Hebron, arguably the most significant southern city in Palestine.

My own work has focused on the diary of Hebronite Sami ‘Amr, who wrote his entries during World War II when he was a young man of 17-21 years old. The publication of Yawmiyyat Sha‘b Filastini: Hayyat Sami ‘Amr, 1941-1945 by the Arab Institute for Research and Publishing (2017) adds to the growing body of historical diaries on Palestine and, in particular, to knowledge about the city of Hebron. Sami’s diary records his entry into adulthood when he left his home in Hebron after completing a seventh-grade education, not uncommon for the time period, to seek work in the British Mandate capital of Jerusalem. It is a “coming-of-age” story in which Sami attempts to further his education, find satisfaction with his job and, ultimately, choose a life partner. Although he includes one prophetic entry about the struggle between Zionists and Arabs in Palestine, Sami’s story is largely free from the politics of conflict. Whether old or young, sitting in a university classroom or reflecting back on one’s earlier days, one cannot help but feel a connection to Sami’s dilemmas about whether to change jobs, to his struggles on how to approach girls, or to his complex views on social life in his native Palestine.

Coming from a conservative environment in Mt. Hebron, Sami writes openly about modernity and tradition, both from a personal and a national perspective. While he challenges his own society in his reflections on relationships and on how Palestinian villages should develop, he also critiques the repressive colonial authority for which he worked, the one that also imprisoned his brother for going AWOL from the British military for which Sa‘di had volunteered to serve. As an older brother, Sa‘di provided him little source of comfort, though Sami loved him dearly and sought all means to ease Sa‘di’s suffering along with the suffering of his mother, much of which was caused by the British colonial apparatus. His father died when Sami was only five years old, so Sami’s mother provided a sense of home and stability for a young man trying to find his place in the world, evident in the letters he wrote to her that appear in his diary. Sami’s hometown of Hebron instilled in him a deep sense of place and his passionate diary entries, as World War II raged, reflect his longing for Hebron. In a number of Sami’s entries, he expresses his desire to return to Hebron, as his work for the British authorities kept him away from his hometown for extended periods of time. While Hebron remains a focal point for Sami throughout the diary, his descriptions of Palestine are an early and an integral historical voice in what has now become a chorus of recently published village memorial books that describe the Palestinian landscape.1

Sami kept his diary in Arabic, but I translated the diary into English, which was subsequently published as a critical edition by University of Texas Press in 2009. My Arabic edition showcases the diary in its near original form and includes Arabic translations of my historical and historiographical introduction. The Arabic edition will serve three important readerships: 1) students of Arabic, 2) native Arabic readers, both students and scholars, and 3) Arabs (non-scholars) who enjoy reading first-person accounts. For students and scholars, this publication adds to the primary source material on the critical period of the British mandate in Palestine, and the World War II period more specifically, just prior to the historical rupture in 1948 from which Palestinians still have not recovered. This young voice from World War II Palestine brings clarity and calm to a people and time period when Palestinians were not viewed, as they so often are in the English-language media today, as terrorists or as refugees. Despite the war, Sami writes of a more mundane life, recording his dissatisfaction with work, disagreements with his family, and wrestling with the cultural expectations surrounding courtship and marriage. All readers can enjoy the entries on family, descriptions of land and holidays, and on the struggles of his youth.

Many people kept diaries during the British Mandate period, including Mandate officials and the notable Palestinian educator, Khalil al-Sakakini. And now Sami ‘Amr’s diary has joined the list of historical diaries published in Arabic. Yet, when he first began to write, it is not clear that he intended the diary to be seen by others, and certainly not the prospect of publication. He simply picked up a copybook, produced in England, which opened from left to right. Sami flipped the notebook over and started from the back of the copybook, which had preprinted numbers on it. That became my system to follow his writing. He did not date every entry and skipped pages when writing particularly long entries. He would return to those skipped pages to add more writing and to add dates. As a result, those entries in the diary are non-sequential and needed reorganization and editing to ensure clarity of the entries. The writing habits of diarists can be idiosyncratic because the texts are not being shaped for an outside readership. Indeed, while Sami’s son, Samir, who requested that I work on his father’s diary and who served as my main interlocutor for questions on the diary, mentioned that his father wanted the diary to be published, it is not clear from the entries themselves that Sami sought publication. Some marginalia, however (likely added later), does indicate this possibility.

In many ways, the diary is an opening for future research. Many topics appear in Sami’s writing that lead scholars to unresolved questions. For example, more research is needed on the role that Palestinian Arabs played in the British military during World War II, including on individuals such as Sami’s brother, Sa’di, who went AWOL. Sa’di went to prison for the crime and this sentence had a deep effect on Sami and his mother. Reading Sami’s diary in its near original form will afford scholars and students alike the opportunity to see through the eyes of this Hebronite, a young man whose writings express his thoughts and deep feelings about his family, his city, and his country during a time of great social and political upheaval.

The Arab Institute for Research and Publishing displayed Yawmiyyat Sha‘b Filastini: Hayyat Sami ‘Amr, 1941-1945 at the annual Middle East Studies Association conference in Washington, D.C. (November 18-21, 2017). It can be ordered at http://neelwafurat.com

Kimberly Katz

Kimberly Katz is Professor of Middle East History at Towson University.

Notes:

1. Rochelle Davis, Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced(Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2011).

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO